An intro to payments: Value, liabilities and networks - Part 1

You are on holiday in another country. You want to buy a coffee.

You get your card out, swipe or type your pin and presto!

Coffee paid for your enjoyment.

Congratulations! You just participated in the modern marvel of international payments.

The simple action described above requires levels upon levels of financial structures and instruments.

This series of 3 posts will attempt to give a high level intro on the history, the “what”, the “how” and, when possible, the “why” of modern payment systems.

Can I has payment?

Some definitions

Photo by Pixabay on Pexels

Let’s start with the very basics: what is a payment?

According to Wikipedia

A payment is the trade of value from one party (such as a person or company) to another…

A-ha! Value. How do we define “value”? Again, Wikipedia helps us with

Economic value is a measure of the benefit provided by a good or service to an economic agent. It is generally measured relative to units of currency…

Hmm. Yet another term: currency. We have

…a currency is a system of money (monetary units) in common use… recognized as stores of value…

The above turns out to be a slightly cyclical definition.

However it becomes clear that the transfer of value in a payment is facilitated by a currency (a.k.a. money).

In other words, money “changing hands” is not a goal in itself. Rather it simply helps in the process of a transaction,

provided that both parties in the transaction recognize money as a trade/store of value. 1

In the olden days…

Photo by Jordan Rowland on Unsplash

Once upon a time, transactions and payments would take place only in person.

Starting in the pre-historic times with barter, mankind quickly had to move to something more handy and attuned

to different types of transactions, some form of money. 2

This role was eventually filled in by precious metals: gold and silver. Precious metals possess a lot of very interesting properties which make them a great fit as an economic medium. That is definitely true for gold and to a certain extent for silver.

The introduction of metals (in the form of ingots, coins etc) as units of exchange solved the inherent accounting problems

of barter and allowed the building of more complex economies. However, it still required a very important thing; the

physical presence and transfer of the metal in order to make a payment.

This is not as easy as it sounds, due to

- the weight of metals themselves, and

- the omnipresent armed bandit behind every bush.

One solution to that was merchant and Templar Knight promisory notes. These solved

- the weight problem: a piece of paper could carry the value of thousands of coins, and

- to an extent the security aspect as well: the issuer could ask for some proof of id.

The logical next step of this innovation was paper money, issued by a central authority.

Both promisory notes and paper money, introduced 2 new concepts:

- An alternative medium for the transfer of value in 3d space (in this case paper).

This acts in lieu of the “real thing”. 3 - A trusted third party facilitating the flow of value.

The trust component being that the third party (merchant, Knight Templar, emperor, central bank) will eventually make good on the promise to deliver the gold, as “written” on the piece of paper.

Money vs. Currency

Going back in time and introducing these basic principles, allows us to examine today with a clearer lens and under a much brighter light.

There are two terms which are used interchangeably in everyday life, even in this text here: money and currency.

With the slight danger of splitting hairs, I will attempt to make a distinction between the two, which I believe

is useful.

Money

Money is something which

- has value in and of itself

- is a facilitator of financial transactions, and

- is globally (or at least very widely) recognised as such.

The archetypal type of money is precious metals, as already mentioned. In the metals’ case, the value is derived by their natural scarcity and the capital and resources spent in extracting them from the ground.

From that aspect, the major proof of work cryptocurrencies can also be considered a digital approximation of money. This is due to the ever-increasing capital and operational expenditure required to mine them.

Currency

On the other hand, currency (in the current definition of the word) is a medium of exchange within a bounded economic area, such as a country. It is the accepted legal tender in that area (many times the only allwoed de jure medium of exchange).

In the modern era, until 1971, the world currency system was underpinned by precious metals.

From that point on, modern currencies (a.k.a fiat money) are only backed by the credibility of their issuing

authority (government and/or central bank). 4

In much simpler words modern currencies are a promise (or, if you prefer, a promise of a promise). It is someone else’s liability to make good on this promise, if the currency is to have any value.

So, to wrap this section up

Money is currency.

Currency is not necessarily money.

Back to payments

Photo by Shukhrat Umarov on Pexels

If one was to depict the global system of payments in a layman way, it would look a lot like a sequence of “barrels”

filled up with “liquid” in a storage room.

These barrels are submerged within larger barrels, which are within even larger ones and so on.

There are a number of different hierarchies of containers in the same room, each one containing a different type of

incompatible liquid (think water and oil).

The containers at the various levels are interconnected with one or more “pipes” allowing the liquid to flow through.

Each of these pipes is equipped with one or more “meters” to measure the flow each way.

In this simplistic mental example

- The liquids are currencies

- The barrels are the various structures which can hold currency: bank account, commercial bank, central bank (from inner- to outer-most)

- The pipes are the ways of facilitating the transfer of currency between accounts and banks.

These are called payment or settlement systems. - The meters are the facilities to keep track of what is moved where and by whom. At their heart these are double-entry ledgers, recording in which direction money moves and who owes what to whom.

There are 2 differences of the global payments system from the mental model of “barrels of liquid”.

- Currency (the liquid) does not physically “move” down the pipes from one account/bank to the other. 5 What actually travel are messages of various types, which result in the ledgers (the meters) recording new transactions and updating balances. In other words, value in today’s payments world is purely virtual and electronic.

- The different liquids (just like currencies) are, well… different and do not mix.

Yet when currency moves across borders, it is the equivalent of water turning into oil. This is a happy corollary of modern-day “money” being electronic. 6

In the olden days of gold-backed currencies, central banks would ultimately settle their balances by gold shipments.

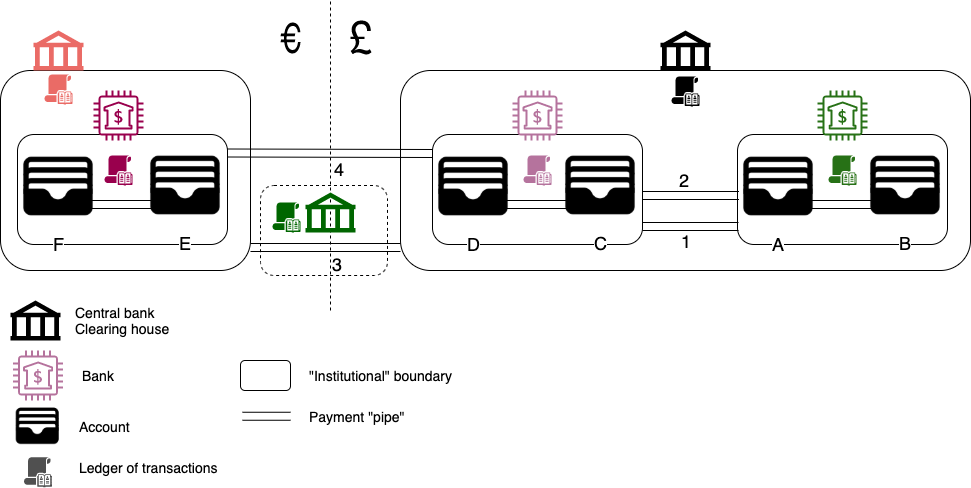

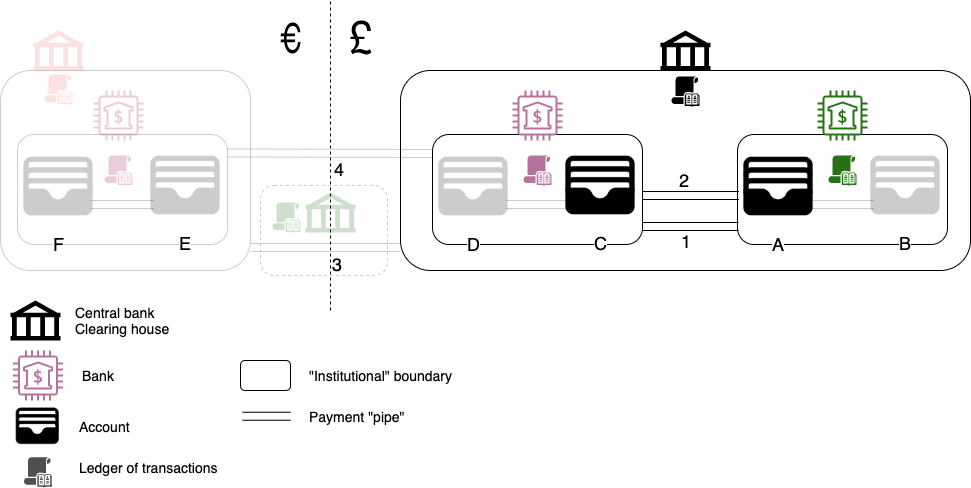

Now that we mastered the simple mental model, let’s jump right into a nice and complex diagram of the modern banking system.

Great, heh!?

Instead of explaining all lines and boxes, let’s see how things interact with a few examples.

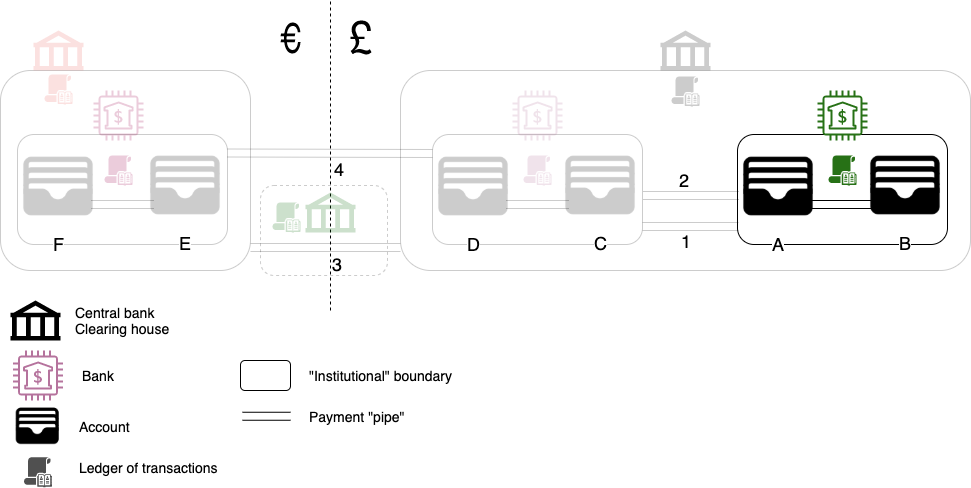

Intrabank payment

Let’s start with the simplest case: a payment from account A to account B, within the same bank. Let’s call this bank GreenBank, or GB for short.

In this case the pipe connecting A and B is GB’s internal systems.

If GB is an older, larger bank, offering more products and most importantly more customer channels, then payments

would probably “settle” as part of large batch operation (usually overnight, at the end of the business day). In this case,

an intrabank transfer is considered final only after the nightly batch has processed every transaction across all channels.

This means that there is a small possibility of the payment being reversed when the system attempts to settle it.

If GB is a bank with newer IT systems and fewer channels (e.g. neobanks), then intrabank payment settlement is in real-time (i.e. when it’s gone from account A, it’s gone).

The transaction (“£50 leave A (debit)”, “£50 go to B (credit)”) is recorded and tracked in GB’s transaction ledger. In the case of overnight settlement, this transaction is first recorded as “tentative” (i.e. the equivalent of “A has £50 payable to B”) and as “settled/cleared” when the batch completes and all has gone well (i.e. “A has paid B £50”). In real-time systems the ledger only contains the settled entries.

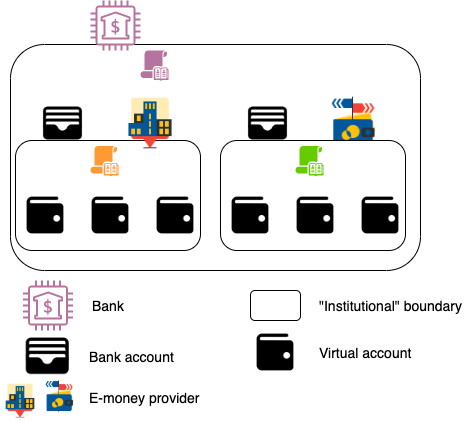

An interesting special case of intrabank payments is that of e-money providers.

Let’s call one of our fictitious e-money provider in this diagram CarrotMoney, or CM for short.

Each CM customer sees their own digital wallet (virtual account, usually a mobile app) with its own balance.

Looking “behind the scenes”, we can see that there is usually a single bank account backing the whole company CM.

This “client money” bank account is held at a “sponsor bank” and contains the money of all of CM’s customers, together

in one lump sum. The only thing that allows CM to know that from, say, the $150 in the client money account $100 belong to Bob and $50

to Alice is its own internal ledger.

In our scenario if Bob decides to send $20 to Alice, then

- the CM ledger will be updated (10 times out of 10 in real-time), and

- their balances on their CM wallets will change.

However from the sponsor bank’s point-of-view nothing will have changed: the CM client money bank account as a whole will still hold $150. The sponsor bank had no transaction to record. It is only when CM customers decide to pay someone outside of the CM “boundary” that the sponsor bank will have to process the payment with its systems and record something in its ledger.

Keeping customer money within their own institutional boundary (a.k.a. “ecosystem”) is a big driver for e-money providers.

This is one of the key reasons why it is a breeze to make payments to other customers of the same e-money provider. 7

CM users may get the impression that money moves around when paying other CM users. However, even if Bob and Alice make

thousands of payments to each other, from CarrotMoney’s point-of-view it is still the same overall amount sitting in the

client account.

Depending on how CM’s business model works and what their customer terms are, this amount can be assets under management,

generating revenue for CM (e.g. accrued interest).

Interbank payment

In the case when a payment needs to go from one bank to another, i.e. across institutional boundaries, we need a third-party to act as the trusted intermediary: the central bank.

Let’s consider the case when account A of GreenBank (GB) wants to make a payment of £50 to account D of PurpleBank (PB).

A number of things need to happen:

- GB needs to make sure that A has at least £50 as available balance

- GB then needs to debit £50 from A

- GB needs to somehow send the money to PB, and

- PB needs to credit £50 to D

From these steps number 3 is the hardest as the 2 institutions need to trust each other. GB will not just send the money in a bag to PB. The questions then are

- How can GB safely “communicate” the money electronically? and

- How can GB payments’ recipient banks (the “counter-parties”) know that GB actually has the £50 and it is not just “spamming” money around (a.k.a. as the double-spend problem)?

The answer comes via one or more secure messaging networks (diagram lines numbered 1 and 2) facilitated and guaranteed by the central bank (over-arching institution, in black). 8

What (roughly) happens is along the following lines

- GB and PB participate in a payment system/scheme, by depositing an amount of money in their account held at the central bank.

- When A’s account holder instructs a £50 payment to D, GB checks the balance of A.

- If A’s balance can cover the payment, GB sends a message to PB saying that “£50 are on their way, I will make you whole”.

- If int the context of a modern scheme, PB credits £50 to D as soon as it receives the message.

- At regular intervals, the central bank gathers all payment messages exchanged between the participating banks, tallies

them up and nets off the amounts.

Outstanding differences are settled by moving money between the banks’ accounts held at the central bank.

At the end of the day, the banks top up that central “stash” if needed and it’s all over again the next day.

In this scenario there are 3 ledgers in 3 different institutions which need to be updated in order for the payment to be tracked

- GB ledger

- Payment from A to B (debit)

- Top-up to/from the central bank (debit or credit, if needed, after netting off)

- PB ledger

- Payment from A to B (credit)

- Top-up to/from the central bank (debit or credit, if needed, after netting off)

- Central bank ledger

- Aggregate movement between CB’s and PB’s central bank “stash”.

The diagram has 2 “pipes” to denote the fact that many countries have multiple electronic interbank payment schemes. For example, in the UK Faster Payments, Bacs, CHAPS,… , in Greece DIAS and IRIS etc.

Newer schemes (e.g. Faster Payments) are message-based and payments arrive in the creditor’s account in a matter of

minutes, if not seconds. Older schemes (e.g. Bacs) are file-based. Instead of messages, all participating banks gather the day’s payments in files

and send them to the central authority for processing and settlement.

Each payment scheme is geared towards a different segment of the payments space. For example, Faster Payments are meant

for smaller value transfers, CHAPS for higher value requiring immediate settlement, IRIS allows defining a payee by mobile

number rather than IBAN etc.

The different payment schemes have developed organically over time to cater for changing market needs.

Because of the fundamental requirement to have a capital buffer in the central bank, not all banks can or want to be direct participants in a payment scheme (e.g. the few current UK Faster Payments participants out of the hundreds of banks, building societies and e-money providers). Therefore any institution wanting to partake in a payment scheme, needs to have a sponsor bank, which essentially provides the plumbing and guarantee for them. 9

Unlike intrabank payments, the only cost of which is running the bank’s systems, the payment schemes usually have a cost per

payment to cover the expenses of running the scheme. In well-functioning banking eco-systems this cost, especially for

small-value transactions, is sometimes absorbed by the banks (e.g. Faster Payments in the UK).

Otherwise this is passed on to the customer, sometimes with sprinkle on top. 10

In our next episode…

Photo by Nicholas Githiri from Pexels

In the next installment, we will examine

- pull instead of push payments, namely direct debit and card payments, and

- how international payments work

Footnotes

- If someone came to you to buy your house with a handful of green beads and shiny mirrors, you would probably say no, even if they called the beads “money”. That is because you may not attribute so much value to them as this imaginary buyer thought.

- Money here refers to the archetypal meaning and definition of the word. If money is not there you end up having to figure out how to buy something with 3.5 live sheep.

- The “real thing” being the gold or silver sitting in the emperor’s or Knights Templar’s vault.

- An extreme example to clarify this point: The people of North Korea are perfectly “happy” to be using the won as a medium of exchange. Their government’s credibility is (literally!) a matter of life and death to them. How much value would you put on a North Korean won banknote and why?

- In the sense that if we make a payment from Japan to the U.S. at no point in time will anyone put yen bank notes in a box and send them over the ocean to complete the transaction.

- One side makes a note “I owe that country X billions” and writes those billions off its central bank balance sheet (the equivalent of “burning money”). The other side makes a note “that country owes me X billions” and adds those in its central bank’s balance sheet (the equivalent of “printing money”). It is slightly more complex than this, but you get the idea.

- Along a newer tech stack and user-focused UX, of course.

- This is a slight over-simplification. In practice the trusted third-party is an institution managing the payment scheme. This institution is setup and sponsored by the central bank.

- This means 2 things:

- In malfuctioning banking eco-systems, this can become an impossible barrier to entry, shielding incumbents from competition.

- On the flip-side of this if, for whatever reason, an indirect participant loses their sponsorship, they will effectively

be shut off from the rest of the country.

Both of these can be strong moats for incumbents.

- It is funny how IRIS was initially advertised as free to use for bank customers, yet Greek banks end up charging regardless.