Scaling Cosmos Blockchains: Putting the Legos together

Scalability is THE differentiator for L1 chain success. In this post, I explore how Cosmos’ modularity can scale a L1 to the next level.

Introduction

Let’s start with a truism.

There is no black-and-white approach to scaling up a blockchain and increasing its throughput (TPS).

Just as with any software system, there is a series of trade-offs to be made, based on restrictions and available tools and technologies. Wearing an architect or senior engineer’s hat on requires us to be aware of both the restrictions as well the technical landscape around us. This will allow us to make informed decisions in the face of uncertainty.

In this post, I will

- lay out some “realistic” requirements of a fictional chain,

- examine the current technological landscape, and

- present an example approach of scaling the chain, while discussing the thought process.

For the readers without a deep understanding of the blockchain space, I will start by quickly introducing some basic

concepts: L1 & L2s, rollups, side-chains, the importance of EVM, etc

If you feel you are well-versed in blockchain concepts, you can just skip to section Setting the stage.

L3, L2, L1, L0… Lift-off!

Photo by Charlie Wollborg on Unsplash

There are different ways we could categorise blockchains.

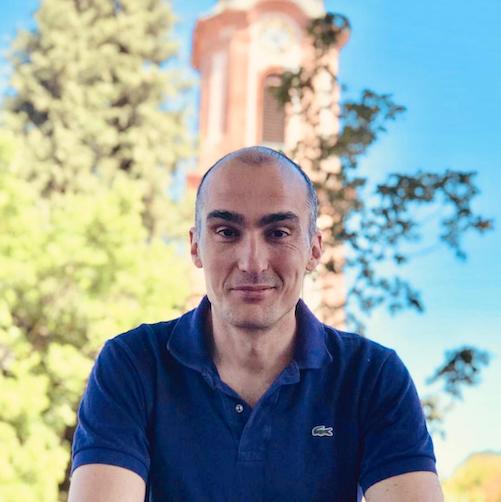

The most common way is by assessing at which point of the “stack” they operate, i.e. at which layer. For this, we will

use the Open Systems Interconnection (OSI) model as a reference.

An attempt to map between the OSI model and the blockchain layers

L1

The 1st (Bitcoin et al) and 2nd generations (Ethereum et al) of blockchains are the first L1 chains.

Whether single-purpose chains (e.g. Bitcoin, allowing transfer of value) or a general purpose chain (e.g. Ethereum,

allowing arbitrary computations), they are all under the L1 category. Their remit covers the whole stack, from

peer-to-peer networking to the top-most user-facing application layer. This category also includes the more recent 3rd

generation chains (e.g. Solana, Binanche Smart Chain, Evmos, Aptos,…). Despite their differences, they all have the

same top-to-bottom “footprint”.

L2

Ethereum’s rising popularity clashed with its fixed transaction-per-second (TPS) limit leading to gas price surges

and a dash to find scaling alternatives.

One of the options was to move the expensive computation off-chain. This led to the creation of L2 chains, which

- perform application computations outside of the L1 chain,

- use the L1 chain as a “source of truth” (e.g. for storing batches of transactions), and

- are interoperable with the L1 chain.

Different L2 solutions (e.g. Optimism, Polygon, Starkware) have different technical choices which lead to different trade-offs in terms of security and decentralization. The end result is one: increase the overall TPS of the underlying L1 chain by moving the expensive computation away from it.

L0

L2s were a solution to the scalability problem, taking the existing L1 chains “for granted”; it is there, it works, let’s

“make it great again”.

L0s are a first-principles approach to the scalability question. They offer the infrastructure and building blocks that comprise a blockchain (p2p networking, transaction finality and consensus, storage,…) to allow them to scale. A L0 is effectively a chain-of-chains; not meant to be used for implementation of user-facing applications, but instead as the foundation for other blockchains.

Through different technology, architecture choices and trade-offs in this category we have Polkadot, Cosmos, LayerZero, Celestia,…

L3

Now that we have described the other layers, it becomes a bit clearer what an L3 is.

L3 is a user-facing application (smart contract dApp) with its own token that is built on top of an L2. There are plenty

of examples here, like Uniswap deployed on Optimism, Decentraland on Polygon, etc.

To the best of my knowledge, we have yet to see a L3 blockchain built on top of an L2. This is because there are no use cases yet which would

- benefit from the increased TPS of the L2, and

- require features that are not available in a sandboxed smart contract environment (like network and DB access)

to justify the creation of an L3 chain, rather than a smart contract.

However, with the increasing adoption of web3, it is only a matter of time that we see an L3 chain built on top of an L2’s SDK.

Rollups and Side-chains: What’s the difference?

Photo by Luigi Pozzoli on Unsplash

Rollups and side-chains are 2 different types of solutions to scale up existing L1s, i.e. increase their TPS capacity. In that regard, they are both L2s.

A rollup utilizes off-L1-chain computation to process transactions. It does this by “rolling up” (read: compressing) multiple transactions into a single on-L1-chain transaction. This reduces the amount of data that needs to be stored and processed on the main blockchain, thereby increasing its scalability. There are 2 types rollups which we will discuss later on: Optimistic Rollups and ZK Rollups.

A side-chain is a separate blockchain, connected to the main L1 blockchain, typically through a two-way peg. This

allows for assets to be transferred between the main blockchain and the side-chain, enabling off-L1-chain transactions

to occur. These off-chain transactions can be processed at a faster rate and with lower fees, while still retaining the

security guarantees of the main blockchain. Unlike the underlying L1 which can be general-purpose, side-chains are

“specialised”; they are designed to be used for specific purposes, e.g. payments, trading,…

Examples of sidechain frameworks are RootStock and Liquid.

Both rollups and side-chains are designed to improve scalability by moving transactions off the underlying L1 blockchain.

They achieve this in different ways.

Rollups bundle multiple transactions together, using the underlying L1 as a storage for the bundle as proof. Side-chains

are separate blockchains, with their own security and consensus mechanism, connected to the main L1. All transactions on

the side-chain are processed and stored off the main L1. What ends up on the L1 is a periodic “summary” of the activity

on the side-chain (i.e. netted off transactions).

Optimistic vs ZK Rollups

Optimistic Rollups are quite simple in their approach. They assume that all proposed transactions are valid and honest; they just include them in the rollup (hence the adjective “optimistic”). To counter bad actors they employ an incentivised fraud proof mechanism: all transactions in the rollup are not finalised for a “challenge period” of a few days. If noone submits a fraud-proof, then they are considered final for all intents and purposes. This simple mechanism allows for fast and cheap computations, at the expense of increased friction when trying to move assets off the optimistic L21.

ZK Rollups on the other hand use zero-knowledge proofs to keep the data private, which allows for private L2 transactions on a public L1 blockchain. The ZK Rollup protocol takes the user’s transaction (or “inputs”) and verifies them with a smart contract. Unlike optimistic rollups which impose a challenge period, ZK rollup transactions are final; the state updates are verified on execution. In addition, through complex zero-knowledge computations (a.k.a. circuits) the proof posted on the L1 chain is orders of magnitude smaller than the optimistic transaction batch2, while remaining private and trustless.

dApps and app-chains

Image from igexsolutions.com

Decentralized applications (dApps) are user-facing applications running on a blockchain.

They almost always have a UI (browser-based or mobile), they use smart contracts to execute tasks and store data, and

they allow for trustless, tamper-proof operations. There are plenty examples of dApps like decentralized exchanges,

prediction markets, DeFi applications,…

Application-specific blockchains (app-chains) can be considered as a variation of dApps. As the name implies, they are sovereign blockchains3 catering to a specific use case or application.

A dApp is generally easier to build and deploy than an app-chain.

dApps only require front-end and smart-contract development knowledge. The logic is then deployed on existing L1 and runs

on the existing infrastructure. The downside is that the dApp is limited by the capabilities of the underlying L1 and

competes for L1 compute resources with other dApps.

On the other hand, app-chains require more involved systems-level programming to implement the code for validators and

nodes. They also require the non-trivial task of bringing together a community of validators which will provide the

necessary infrastructure to run the chain. The upside is that an app-chain leads to more efficient and scalable solutions

for certain types of applications, allowing the core team to tweak with any aspect of operations (consensus, tech stack,

tokenomics,…).

A good example of the trade-offs in the decision-making is the case of dYdX. They started out as a dApp on the

Ethereum ecosystem, but eventually decided to build their own app-chain to improve their scalability and performance.

Developers, developers, developers

Image from tenor.co

Key to success for every general purpose chain (L1 or L2) is the developer community and the developer experience.

How easy is it to build on the platform?

How easy is it to deploy and maintain the application?

What tools are there to support in the development lifecycle?

Can the team find skilled engineers or would they need to upskill in a new technology stack?

These (and more!) are concerns which are crucial to the uptake of a blockchain platform by engineers. As the motto goes “Builders will BUIDL”; it is these new applications and systems that will attract new users and volume to the underlying blockchain and increase its token’s utilisation.

Ethereum’s Solidity smart contract programming language and the underlying Ethereum Virtual Machine (EVM) have been around the longest and they (arguably!) provide a superior developer experience compared to other smart contract platforms.

Solidity is a high-level programming language, i.e. closer to human-readable code. It has historically been easier for non-crypto developers to pick up, understand and work with. This, along with Ethereum’s head start compared to all other smart contract platfroms, has resulted in a much larger and more active developer community. This translates into a large number of tools, libraries, and resources for Solidity developers, which hugely accelerates the development effort.

The result is that there is a huge number of dApps built on EVM on its blockchain compared to any other platform.

According to DappRadar there are almost 4,000 EVM dApps built on Ethereum. Combined with other EVM-compatible

chains like BSC, Cronos etc the number climbs closer to 10,000.

For contrast, competing non-EVM-based platforms like EOS and Tron have 1-to-2 orders of magnitude less

deployed dApps.

That is a huge hurdle for any new development platform with its own language to overcome, in terms of tooling quality, community support and available talent pool. As an anecdote, AI coding assistants (Github Copilot, ChatGPT) offer much better support with Solidity than any other smart contract language.4

So, in conclusion, easier developer adoption and a better upfront developer experience mean that EVM compatibility should be top-of-mind.

Setting the stage

Photo by Annie Spratt on Unsplash

With our basics out of the way, let’s set the stage for where we are and what we want to achieve.

We will first discuss an ideal end state (a Vision) as a direction of travel. Then we will set out some requirements or

constraints (a Mission) to guide us through this journey.

Let’s start by time-travelling to the future and start with the…

Vision

Here is a very bold assertion.

In a few years there will be millions of dApps, tokens and L3 chains, tokenizing and representing any asset imaginable.

Let’s work backwards from this statement.

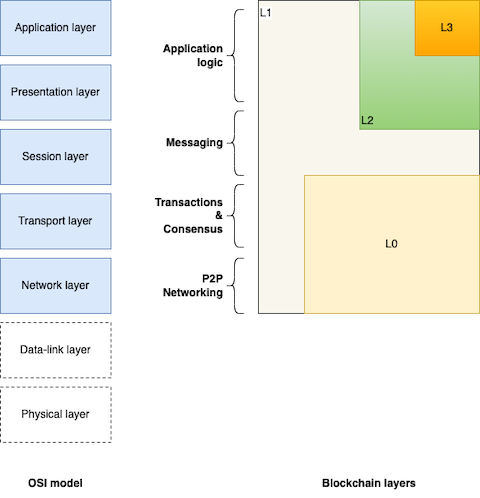

The Internet gives us a good prior example of exponential technology adoption. The number of websites has been on an

exponential trajectory for the last 20 years. From 0 at the beginning of the ’90s to almost 2 billion today.

Chart from Statista

Web2 websites (and online systems in general) are a great parallel to web3 dApps and chains. They are both collections of data and logic, with progressively higher orders of user engagement and utility.

The crypto space is clearly following the Internet adoption curve, no matter which metric we pick. This has two important consequences for aspiring general-purpose L1s.

-

Volumes

That is an obvious one: L1s must be able to support exponentially growing volumes of transactions. -

Flexibility

Just like websites range from simple Wordpress sites to gigantic banking and e-commerce systems, future dApps and L3s will come with a continuum of needs- from maximum-3rd-party-trust-with-little-on-chain (Wordpress-like) to minimum-trust-with-everything-on-chain (banking-like), and

- from few large Bitcoin-like “transactions” to millions of gaming-like “micro-interactions”

L1s that aspire to take market share should have the performance, building blocks and tooling to enable this future for their users and developers.

Preparing for the journey

Now that we have the destination, let’s define our starting point and set some requirements for the “journey”.

Starting point

I will call both our imaginary chain and its token XYZ.5

The XYZ chain is a well-established player in the wider blockchain ecosystem.

It already has a few million users (active addresses) on it. Almost the entirety of this user base comes from a very successful single app, to which they are very loyal.6 This gives it a good moat compared to the competition and a ready user community with which to entice 3rd party developers.

XYZ is implemented using the Cosmos SDK and allows EVM-compatible smart contract development. It already has a

number of dApps deployed on it and has a reputation for stability. However, it ranks lower than other L1s in number of dApps

deployed.

It has a high market cap, say top 50 or top 20; in other words it is significant. On the other hand, its DeFi ecosystem is

not as developed: the Total Value Locked (TVL) is low compared to other chains.

In summary, XYZ’s team have “something” in their hands; they do not start from zero. There is an existing user base, which should not be jeopardised. Any decision has to consider not only the upside opportunity, but also the downside risk.

Requirements & Priorities

Based on the discussion so far, we have some realistic requirements. Let’s list them briefly, in semi-random order.

-

Tech stack Our chain is built using the Cosmos SDK, so there is existing know-how in the team and the ecosystem.

Any decision on changing the tech stack should not be taken lightly. -

North star metric

We need a quantifiable target to act as a “North star” measure of scalability progress. This is how both internal teams as well as the community will unambiguously assess the success of the effort.The most obvious and widely understood metric is transaction throughput. The target figure must be maintained under various network loads and conditions. Therefore instead of aiming for transactions per second (which could fluctuate wildly), it is better to aim and measure transactions per day (where noise can be smoothed out).

A corollary of aiming for a specific throughput, is that the team would need to have a dedicated stress-test harness system. This will allow them to test candidate technical solutions and to gage early if they would bring the system closer to the goal.

-

Stability » bleeding edge

This is a general guiding principle, a value.

As discussed in Starting point the chain’s moat is the existing user base. In that regard, the technical team has to seriously consider the potential downside of any risky or untested technical solution. Any technological improvements will not be done for technology’s sake; instead technology is the tool to maintain and expand the existing user base. -

Based on “serious” open source

This is a restriction, which comes as a natural corollary of the above principle. If a chain’s (or any product/service for that matter), USP is not cutting-edge technology, then the chain is an integrator rather than an inventor.7 Any technical enhancements and new building blocks should map to well-maintained open-source repositories. -

EVM compatibility

This is a 1-way door decision. In the Cosmos ecosystem there is the optionality of integrating different smart contract VMs (EVM, CosmWasm, Gno.land). In practice this is a decision which has far-reaching consequences in the execution and future adoption by developers.

As discussed in the Introduction, the EVM/Solidity ecosystem has the best developer experience by far, through sheer community size and tooling availability.

Therefore, XYZ chain will find it hard to economically compete for developer attention8 if it does not continue to offer EVM compatibility. -

Bridges to other chains

This is another thing to keep in mind: interoperability across chains increases the reach and utility of an L1. On the other hand cross-chain bridges remain one of the biggest sources of vulnerabilities in the blockchain world. This further restricts the technology choices in the current landscape. The Cosmos SDK offers secure, native bridging via IBC out-of-the-box. Reaching to other blockchain ecosystems requires either technology-enabled native bridging, or maintaining compatibility with existing, battle-tested bridges.

IBC-enabled chain interactions, by mapofzones.com

-

Compound XYZ token utility

This is another guiding principle. Almost all L1s (XYZ included) start their existence with a genesis token distribution, part of which goes to the team’s treasury. This works towards aligning incentives for long-term success.

In an existing and developed ecosystem, like XYZ, there is a strategic intent to not “cannibalize” the existing token, e.g. by introducing a dependency to a new or 3rd party token. The goal must instead be to compound value. This works in favour of everyone involved: tokens in treasury, RoI for partners’ validation infrastructure, ecosystem participants.

In brief, any solution must avoid any dependency on external tokens or dilution of utility of the existing XYZ token. -

Single, composable chain

Last but not least, XYZ chain should remain a composable chain. This is another 1-way door decision. A chain can increase its throughput via side-chains or channels (e.g. Lightning for Bitcoin). These channels are extremely effective when the chain is single-purpose (like value transfer for Bitcoin). In general-purpose chains introducing use-case-specific side channels can quickly lead to confusion and poor choices.

Should there be a side-chain per market vertical (e.g. gaming, DeFi)?

Or per transaction type?

How do ecosystem participants decide correctly which one to join?

Moving forward

Photo by NASA on Unsplash

Now that we have established some guiding principles and requirements, we can start to look at the options available

to us.

Let’s start with some…

Low-hanging fruit

Cosmos SDK & Tendermint improvements

Upstream improvements is part-and-parcel of a vibrant ecosystem, like Tendermint Core.

These range from peer-to-peer networking improvements, to upgrades of the ABCI interface and mempool prioritisation

refactoring.

Keeping up with these is a must, as they will inevitably bring some performance improvements to the chain.

Block adjustments

This is another place to look.

- Increasing the block size (“how many transactions can we fit”)

- How frequently blocks are minted at the consensus layer, and

- Tweaking the block creation logic

are all pulls and levers which can potentially increase throughput.

There are two things to note with all of these:

- They are all incremental performance optimisations, not step changes. Performance will probably increase as a percentage, not by a factor of 2-3-10x.

- There are diminishing returns to each of these. They all directly affect the requirements on the validator nodes capacity and connectivity. There is a cut-off point where it might become unfeasible to run a validator node, if the block adjustment are out of whack.

Storage logic optimization

A large part of validator node resources is consumed by managing and storing the chain’s state in the local database.

In the Cosmos SDK, all building blocks of logic (a.k.a modules) store their data in the internal key-value store.

Some modules will have a disproportionate load on the node and will become critical (e.g. the EVM module, an order book

module in a DEX chain, etc).

Focusing on optimising the storage of these modules (e.g. optimising data structures, decoupling from the default

storage) can potentially bring performance improvements.

With quick wins out of the way, we need to think of potentials for step change; orders of magnitude improvements.

Let’s look at some more ambitious options.

Option 1 - Parallelisation of execution

At transaction settlement

The latest generation of general-purpose chains like Zilliqa, Aptos and Sui have a USP of higher

throughput via parallelisation of transaction settlement.

This parallelisation is based on the insight that most transactions in the same block affect different parts of the

global state graph9. This parallelisation is made possible either via explicit transaction

classification (Zilliqa10) or by optimistic locking of the global state and hard-coding

inter-contract dependencies (Aptos, Sui11).

Transaction settlement parallelisation definitely sounds appealing. Let’s take a step back and assess it in the context

of our imaginary chain.

Being a Cosmos chain means using the Tendermint BFT consensus algorithm, which has sequential execution. Moving

to parallel settlement would entail a complete re-write of the underlying consensus layer.

Even with the availability of

ABCI++, all transactions would have to be decoded in order to be introspected and categorised. The changes in transaction

settlement (from instant finality to eventual settlement) would affect the logic of a large number of SDK modules (Bank

module for account balances, EVM for smart contracts,…).

Though not impossible, this is a major undertaking. And it would contravene our guiding principles of stability and utilising existing technologies.

At EVM execution

In general computation chains, the vast majority of transactions are smart contract operations. And EVM execution is by far the most expensive part of the transaction settlement. Therefore it makes sense to focus on that.

From an architecture PoV, parallelization of EVM execution seems like a more contained piece of work. EVM is implemented

as a Cosmos SDK module, so all changes should remain transparent to the rest of the codebase.

From an implementation perspective, a core piece of work would

be to understand the impact of transactions on the state graph of the EVM and identify which ones can be safely executed.

Transaction classification can range from explicit and standards-based (e.g. see EIP-2930) to implicit and esoteric

(e.g. bytecode heuristics12).

In terms of implementation options there are a couple.

Ethereum adoption of EIP-2930 will “force” the corresponding work on the Cosmos EVM side to maintain compatibility. This

would provide the needed open-source support, but it is still unknown when it would actually happen.

Another real-world option is NodeReal’s Parallel EVM adopted by Binance Smart Chain. On the downside NodeReal’s EVM

would need some work before becoming usable by another chain.

Though not immediately going against any of the principles laid above, there are a couple of risks to consider.

- There is no drop-in Cosmos module for parallelised EVM execution just yet. The XYZ team will need to do some extensive investigation and PoCs to proceed with confidence. The eventual result would require 3rd-party security audits before going on mainnet. In the extreme case that the upstream Cosmos modules would not accept the pull requests, the chain’s team would need to maintain an EVM fork on their own. That would be against priority 4).

- On low chain loads, overall performance may actually decrease after the parallelisation upgrades. This might be perceived wrongly by the community. See the Aptos whitepaper findings.

In general the parallelisation of EVM execution is a promising path to explore. It should be part of the chain’s optimisation journey.

Option 2 - Data availability (storage modularization)

As we touched briefly in Low-hanging fruit, the storage element is a major contributor to resource

comsumption. In other words, a performance drag.

Increasing blockchain speed by offloading block storage to an external component or service has been studied at length,

especially by the Ethereum community. Mostly referenced in the context of a ZK rollup (to be discussed

later on), a data availability layer can accelerate any chain connected to it. Our XYZ chain is already a general

computation chain, appealing to high-throughput and possibly high data volume apps, like gaming.

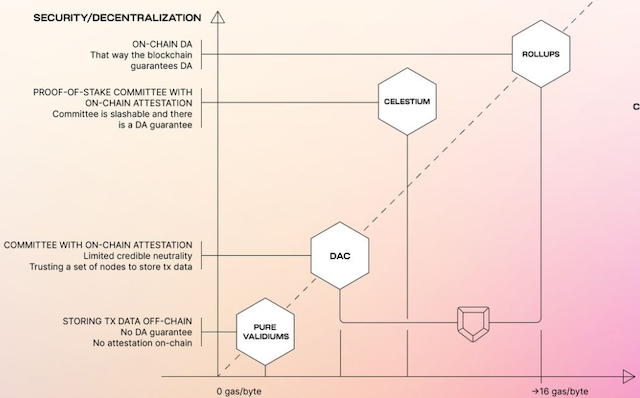

It is worth pausing to think that dApp storage needs are not one-size-fits-all. They fall along a “ladder” of increasing complexity and security13. In the ideal end state, in our XYZ chain

- different dApps will have access to different storage options, depending on their needs, and

- access to the data availability layer is abstracted behind an SDK.

For these reasons it makes sense to investigate storage availability as a separate building block, rather than making it a “blocking” requirement in the chain’s roadmap. Let’s dig in a little deeper.

From a code PoV there is an actively maintained Cosmos-compatible reference implementation of a base storage layer:

Celestia. Celestia is built from the ground up as a L0 and will eventually have its own token; using it outright

would be against Priority 7. On the other hand, Celestia’s code itself is built in a modular way, courtesy

of Cosmos SDK and Go.

This means that the XYZ chain team can use a Celestia fork as a PoC starting point and investigate

- the extent of out-of-the-box reusability vs custom development with regards to Cosmos SDK modules,

- the impact of the data availability layer on the chain’s performance,

- the feasibility and best way to introduce various data availability models (Validium, DAC,…) via a common interface, and

- (in the case of the DAC option) the best tokenomics model, if applicable. I.e. should DAC be secured via simple proof-of-authority, re-use the existing XYZ token or introduce a separate DAC.

Even with plenty of research and a working implementation to begin with, there are a couple of risks to consider here.

- The existing Celestia codebase may be hard-to-impossible to incorporate. This would mean starting the development from scratch, which is against Priorities 3 and 4.

- The chosen implementation approach of a DAC does not align with the interests of XYZ’s partner validators (e.g. incentives, infrastructure choices,…). In other words, they would not want to support it. This can be mitigated by involving the community from the early stages of the high-level DAC design and any tokenomics decision.

- The interface and functional choices of the data availability module/SDK is not fit-for-purpose for the needs of the

community. Like with any product, there will be a fair amount of assumptions baked in (e.g. will there be a lot of

gaming apps? If yes, what will their on-chain usage profile be?) The long lead time of infrastructure products may not

agree with the fast-shifting pace of the blockchain space. This uncertainty can be mitigated by

- circulating the design ahead of time for comments from the community, and

- the XYZ chain team creating some realistic dApps (themselves or via a commissioned 3rd party) to verify the usability of the data layer.

Option 3 - Rollups

The third option is to use a rollup technology.

This involves a couple of important upfront decisions.

ZK vs Optimistic Rollup

This is a major one-way door decision.

The two technologies offer similar benefits, but are not interchangeable. We discussed their characteristics in the

Introduction section ZK vs Optimistic.

From the XYZ chain’s PoV both appear to offer benefits.

- Optimistic rollups offer simple implementation, aligning with Priority 3 of prioritising stability.

- On the other hand, optimistic rollups’s securirty is effectively a product of social consensus and participant incentives. If, for some reason, fraud proofs are not submitted, the whole security model falls apart.

- ZK rollups’ security is firmly grounded in mathematics. This makes it a more reliable long-term option. The security is harder to implement, but not open to disputes. This aligns well with Priority 3 in the long term.

Weighing the choices and their trade-offs, it would make sense for XYZ chain to pursue ZK Rollups.

EVM compatibility

The second decision is whether to use an EVM-compatible rollup or not.

Requirement 5 is unambiguous on this: yes.

Which, given the discussion on ZK rollups we just had, brings us to the next question: can we have an EVM-compatible ZK rollup? The answer is also yes.

zk-VM implementations are split in 2 categories:

- 1st generation VMs. These ones employ a bespoke language to support the underlying ZK execution semantics (e.g. Starkware’s Cairo)

- An emerging cluster of 2nd generation VMs. These offer full EVM compatibility out-of-the-box.

Examples here are zkSync, Polygon Hermez and Scroll.

From the XYZ chain’s PoV, Priority 5 points not only to EVM compatibility, but cross-stack developer tooling

compatibility and re-use. I.e. giving dApps the ability to port across chains with minimal-to-no changes.

This makes a zk-EVM a better choice, with 3 different option to explore.

At the time of writing this article, the state of the 3 options is as follows.

- zkSync

Currently at mainnet. Critical parts of the code (e.g. Prover) are not available, while others do not build intentionally. Critical parts of the code (Prover) are not available, while others do not build intentionally. This makes the project effectively closed source, due to its strategy14. - Scroll

At pre-alpha testnet. Fully open source, but with zero documentation at the time of writing. From a quick glance it appears to be at least 1 year behind zkSync in terms of code maturity. - Polygon Hermez

Currently at testnet. This EVM is the best documented of the 3, with almost 100% EVM opcode coverage and all code open-source.

It seems like the most promising option of the 3.

Rollups and the XYZ chain

The way forward for the implementation of rollups in XYZ chain becomes a bit clearer.

The team would need to deploy a separate L2, secured by the existing XYZ chain. Let’s call this XYZ v2.

XYZ v2 would offer ZK rollups along with full EVM compatibility. This would allow existing XYZ chain dApps to be ported over with minimal changes.

It is also important to highlight a future strategic opportunity with ZK Rollups.

A standardization of circuit/prover logic across ecosystems would lead to (almost) native bridging of assets between

compatible zk-Rollups, regardless which chain ecosystem they are implemented in. This would fit nicely with Priority 6.

This is something worth exploring by thge XYZ chain through cross-chain technology partnerships.

Like all choices, rollups also come with their own risks.

- Maybe none of the 3 ZK EVM options are ready for use within XYZ chain’s timeframe.

E.g. zkSync remains closed source for an unknown period of time, Polygon has bugs, etc. This could be a real threat to the delivery of this milestone. A possible mitigation would be to join forces with one of the above teams to assist. - Not all ZK circuits are created the same; the chosen prover circuit may not be performant enough.

For example, it may require specialized hardware to run (see footnote 14). This could lead to validator centralisation.

This is an area that requires active R&D and leveraging partnerships in order to derisk.

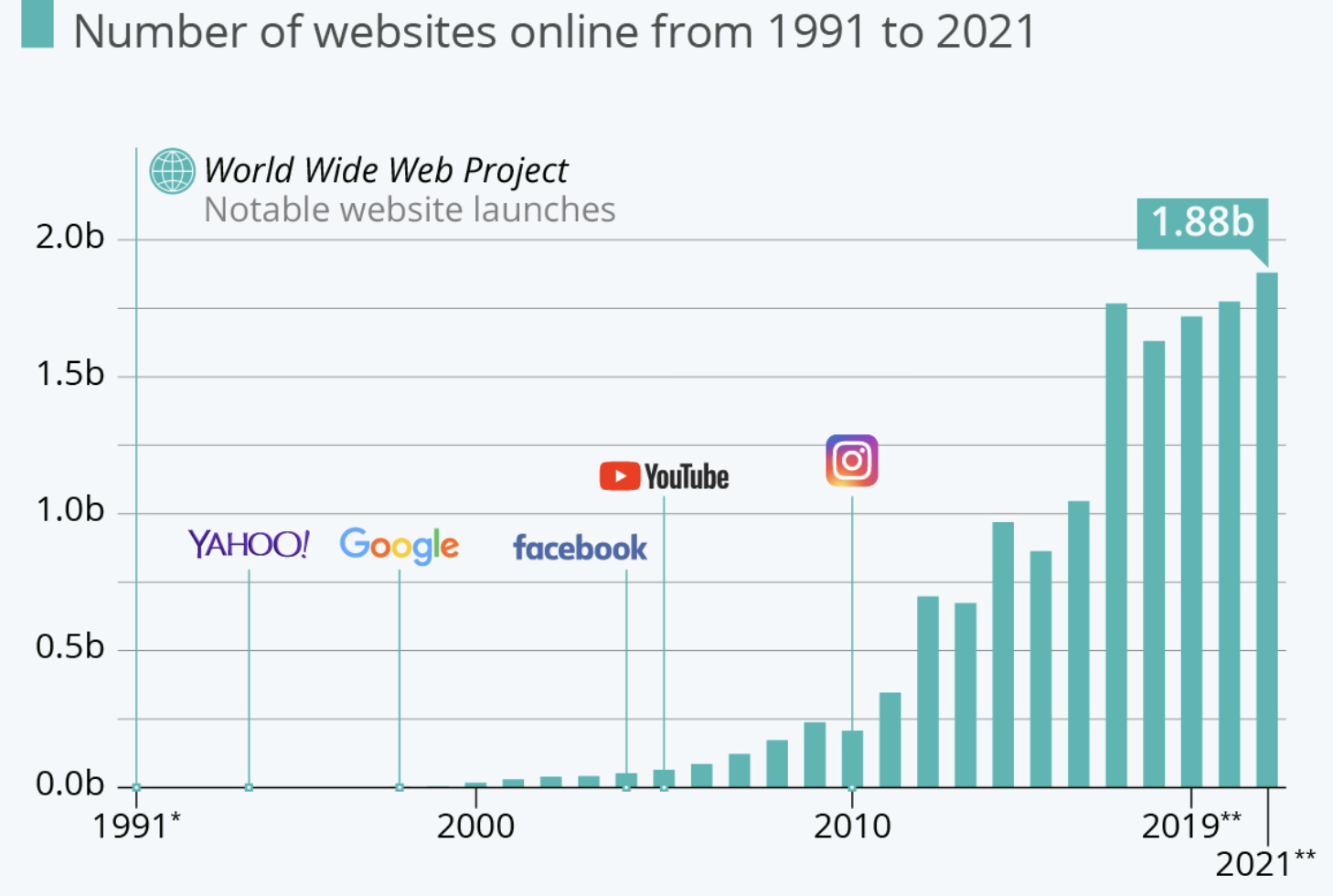

A path forward

With all the pieces in place, the last thing to do is to put them together in a coherent plan.

In a key piece of infrastructure like a chain, having a clear plan with milestones and a target end state is key to

building up trust in the stakeholder community.

Expansion phases and building blocks of the XYZ chain

This diagram attempts to do 3 things:

- depict the new building blocks of the XYZ chain that we just discussed and how they correlate to each other,

- group them together in a rough plan with delivery milestones, and

- highlight the touch-points with external pieces of infrastructure.

In terms of sequencing and timing, the different phases can be sequential or have any amount of timing overlap. This depends entirely on the capacity of the XYZ team and the availability/maturity of external components.

Phase 1

Here we have grouped together all the improvements described in the section Low-hanging fruit.

These are the internal optimisations to the existing codebase of XYZ.

The chain will continue maintaining support with other L1s via IBC, Gravity Bridge and, for Polkadot chains,

XCVM.

Phase 2

In this milestone the XYZ team can tackle the Parallelized EVM work. Once completed, this would deliver an additional performance

boost to the chain’s throughput.

Phase 3

This phase delivers the Data Availability layer (DAC) as a separate building block.

It offers an SDK for its various modes (centralised validium, fully staked DAC). The SDK, delivering the simplest forms

of storage first, would allow dApps on XYZ to start developing straight away (for example, gaming requiring

semi-centralised rather than independently attested storage).

Depending on the uptake, this will also help improve the XYZ chain throughput, nearing towards the North Star

performance goal.

Phase 4

This will deliver the zk-EVM functionality as a separate L2 on top of XYZ (after evaluating all alternatives).

Depending on delivery timing and community interest, the new L2 chain may also utilize the DAC SDK & layer for storage.

Other items

- Tooling

The delivery of the above phases is not in isolation. Instead, it is accompanied by updates to a number of tools and interfaces: wallets, SDKs, dev tooling and documentation. Their delivery cycle and feature set is aligned to the delivery phases of the XYZ chain. - ZK cross-chain bridge

This is a “later” thing, to be delivered sometime in the future. Once zk-EVMs and ZK chains in general proliferate, this will be the next area to get R&D focus. Compatibility at the prover & circuit level will lead to native bridging of assets.

Parting thought

Photo by Mar Bocatcat on Unsplash

And that was it! 🎉🎉

We covered a LOT of ground in this article.

For someone new to the space, it may have been a bit overwhelming or even complete alien language.

The point was not to understand every little detail. Instead it was to get a sense of the different options available in the little corner called Cosmos ecosystem and how they can fit in a decision framework.

If you are going to have only a single take-away from this article it should be this: blockchain not only a space of

non-stop innovation.

It also has its own tradeoffs and optimisations based on external factors.

The best choice is the one that fits the problem at hand.

Just as in any discipline of engineering.

Until next time, keep building!

Footnotes

- Normally assets cannot be moved out of the optimistic L2 and back to the underlying L1 for the duration of the challenge period. However a number of bridges allow for fast exits-for-a-fee, with the liquidity providers taking on the risk of the challenge period.

- An extremely simplistic parallel of a ZK proof’s size is to a hash. A hash is much smaller than the original data, but still uniquely identifying it.

- Sovereign meaning having their own set of validators, consensus mechanism, token and governance.

- As an experiment, try asking ChatGPT to create a simple smart contract in any other smart contract language. Chances are it will return a Solidity example on its first attempt.

- It would have been easy to start from a “blank sheet of paper” with a new chain. But it is rarely realistic to be discussing technology in a vacuum. There is always some context which informs our decisions and trade-offs. The whole point of this thought exercise is to see how we can reach a technical “destination” in the face of different restrictions as well as options.

- There are plenty of examples of single “killer” apps acting as on-ramp for users on a chain: Stepn for Solana, Sweatcoin on Near, etc

- It is worth re-stating here the difference between invention and innovation. Something I have covered in my investment-related blog posts.

- It is important stress the word “economically” in this context. Chains introducing new smart contract languages will need to invest a lot of time and effort to educate developers on the new language. This inevitably translates into a lot of community marketing and development effort (articles, hackathons, grants). This is a game for deep-pocketed chain teams.

- 2 simple examples of transactions happening in the same block:

- Alice sends tokens to Max. Alice sends tokens to Bob. Alice’s balance is affected by both these transactions, so they have to be executed sequentially.

- Alice sends to Max. Bob sends to Dave. The transactions affect separate balances, so they can be executed in parallel.

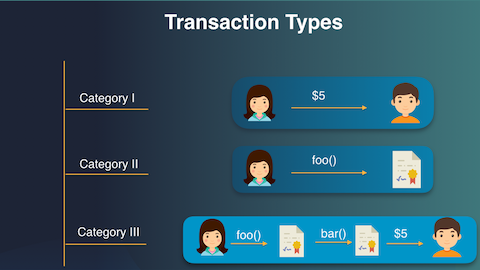

- Zilliqa classifies transactions as:

- account-to-account

- account-to-contract

- complex (account-to-contract-to-contract-to…)

This allows the chain to understand the “impact” of each type of transaction and batch/shard accordingly.

Image from Zilliqa

- Both chains are Diem spinoffs and follow similar design approaches.

Their internal data model is using optimistic state locking to support parallel transaction execution (versioned data items). This results in “eventually settled” transactions. - Performing bytecode analysis to discover state graph dependencies (e.g. F1, F2,… opcodes)

-

Data storage is a continuum of choices.

At one end we can have a centralised off-chain DB, either fully trusted or providing Validium-like ZK proofs for maximum speed, to Data Availability Committees (staked & unstaked) to full on-chain ZK rollups.

Image from Celestia

- According to zkSync’s CPO, achieving performance on generalized hardware is their “technical moat” and the most closely guarded part of their codebase for the foreseeable future.