An intro to payments: Value, liabilities and networks - Part 3

In this post I will

- cover modern payment “rails”,

- blockchain-based systems, and

- close the “trilogy” with some parting thoughts on the future and how the unfolding Covid-19 pandemic will accelerate the evolution of the payment systems.

In the previous 2 instalments (1, 2) of this series, I talked about the history behind payment systems and described how domestic and international payments work.

E-money

M-Pesa

Mobile money (or M-Pesa as is widely known from its initial Kenyan incarnation) is the answer to the question

How do you provide digital financial services to third world populations, where the only technological device available is an indestructible brick phone?

It seems that the populations had already found the answer themselves: swapping of airtime.

M-Pesa is just the glossy version of an existing unofficial practice.

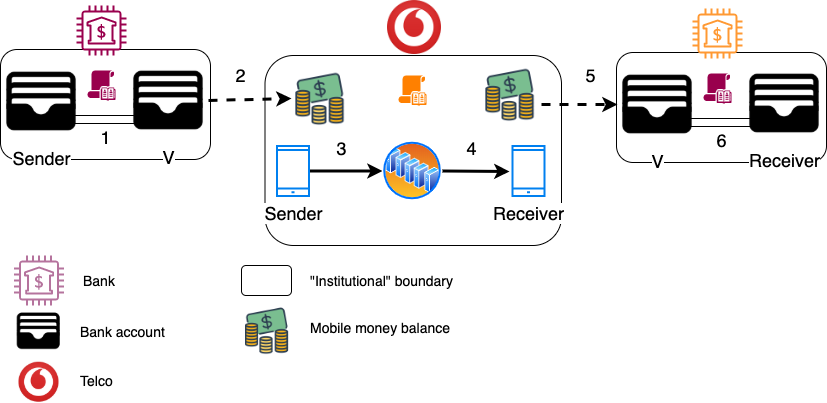

Let’s see how it works in principle.

- The Sender wants to top up her mobile money account balance.

She sends the equivalent amount to the Telco’s bank account (V). - The Telco is notified that a new deposit was made and increases the Sender’s mobile money balance.

- The Sender can now make a payment using M-Pesa’s mechanisms to the Receiver (e.g. using an STK application with secure SMS).

- The transaction is recorded on the Telco’s ledger and the account balances between Sender and Receiver are adjusted.

The Receiver can use the balance for a mobile payment in the ecosystem or convert the amount into “real world” money, which is then paid to her account (lines 5, 6).

From its inception, M-Pesa was meant to be an on-ramp / off-ramp system, parallel to the “real”

financial world. In practice, even to this day, the off-ramping (5, 6) is rarely, if ever, exercised. This is a

combination of the plain lack of bank accounts in developing markets and the exorbitant withdrawal costs.

This last statement reveals a gross simplification of the above diagram: the vast majority of on- / off-ramping

does not happen through bank accounts. It takes place through a vast network of street agents, who convert

cash into mobile money, taking a commission.

Street agents are the equivalent of a bank’s brick-and-mortar network. The extremely low capex

to setup an agency gave telcos an advantage of quick scale.

Since everything happens within one IT system (the telco’s servers), transfer and settlement is instant. This is

combined with the mobile phone’s PIN, providing a rudimentary layer of security.

This level of convenience and the lack of a viable alternative, led to African telcos becoming the de-facto

financial infrastructure is some countries. 1 This ubiquity makes the off-ramp

almost unnecessary. It took years for the West to achieve a similar level of customer convenience.

Despite their importance and the huge commissions made, telcos were very lightly regulated in most countries until recently. Concepts like segregation of funds are only now being addressed, with telcos held to the same standard as banks have been.

Super apps

Super apps is a relatively recent term, describing mobile apps developed in East and South East Asia. They are worth mentioning here, due to their rapid growth.

Not originally conceived as payment rails, they have moved into payments and financial services in recent years. They then quickly grew to rival banks in terms of transaction volume. Some examples are WeChat and Alipay 2 in China, PayTM in India and GoJek in Singapore/Indonesia.

The underlying mechanics of this payment rail are pretty much identical to those of M-Pesa.

App users can fund their account with a variety of means: from a normal debit/credit card all the way to the ojek driver becoming

an agent on wheels. The payment system is a general ledger running inside the company’s domain, tracking transfers

of value between users.

The demographic and economic tailwinds of the region have enabled them to grow into massive user bases and are now

rapidly expanding into all kinds of financial services, beyond payments (lending, credit scores,…).

Especially in the case of China (a prime example of command economy), WeChat and Alipay have become deeply integrated

with the state apparatus, offering unique insights for the social credit score system.

M-Pesa was created because of the lack of a viable alternative for payments in its home countries and keeps on growing on the back of that. Super apps started with a killer core feature 3 and are now growing on the back of innovation and the irresistible power of the network effect.

Paypal & friends

The wave of internet e-money providers like Paypal started in the early ’00s to facilitate transactions in the

growing online commerce sector.

Focusing on UX and web integration, they grew along with the growth of the internet. Paypal, through its affiliation with

eBay, focused early on the online commerce sector, establishing a user base of millions of merchants and users.

Paypal is also an on-ramp/off-ramp system.

Since all transactions between Paypal holders take place within the company’s ledger, settlement (and credit to the

merchant’s account) is instant. This was a great value proposition in the early days as the US retail banking system is

notoriously inefficient and online card fraud was rampant.

Paypal provided a trusted third party, which would guarantee customer payments until they cleared from the bank, with an

internet-friendly e-mail based identity.

As the underlying “plumbing” improves and the e-money and payment processing space get crowded, the initial value proposition is reduced. Paypal ends up being another middleman among many.

OpenBanking

OpenBanking is a broad term which refers to

The use of open APIs that enable third-party developers to build applications and services around the financial institution.

The UK regulator decided in 2016 to front-run the upcoming pan-European PSD2 directive, which was coming into full effect in September 2019. The name of the UK initiative, OpenBanking, has now become almost global and describes open financial APIs, offered by banks.

At its core OpenBanking enables bank customers to perform all their banking tasks through a third party’s application.

Though it provides access to data as well as payments, I will be focusing on the latter in this section.

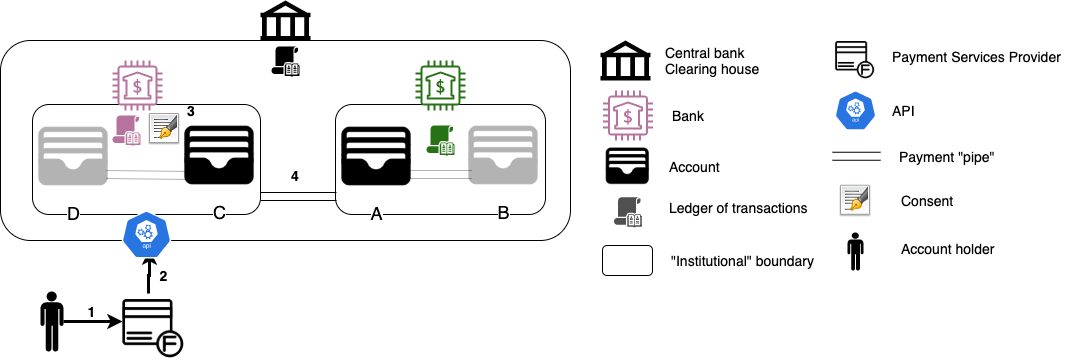

The following diagram gives an overview of how it works.

- A Customer registers with the application of a PSP.

Practically any app could be a PSP; from a mobile-only personal finance assistance (e.g. Plum) to a payments processing platform (e.g. Adyen). - The Customer wants to initiate a payment from her account (C) in PinkBank to another account (A), using the PSP.

The PSP’s app calls PinkBank’s standardized OpenBanking APIs. - Following the standardized OpenBanking customer consent flow, the Customer agrees that the PSP initiates the payment (to the given Receiver account and for the given amount) on her (the Customer’s) behalf. The consent is stored in PinkBank’s systems.

- The PSP then instructs PinkBank to initiate the payment.

Depending on the payment’s type (domestic, international,…) one of the existing, underlying payment schemes is used.

From the above it becomes clear that OpenBanking is not a new “payment rail” as such.

Rather it is a technological layer on top of the existing banking infrastructure, opening access to a number of new

companies (the PSPs). Though the aim is for better customer service and control, the result is disintermediating the

customer from the bank (by introducing additional “smart apps”).

This will eventually lead to the commoditization of the banking institutions (in a way similar to how Booking

and Airbnb have commoditized the hospitality sector).

Remittance services

We saw in part 2 how complex (and more often than not complicated) international payments are.

What if there was a magic way of sending value cross-border without anything actually crossing borders?

Sounds weird? This is where remittance services come in.

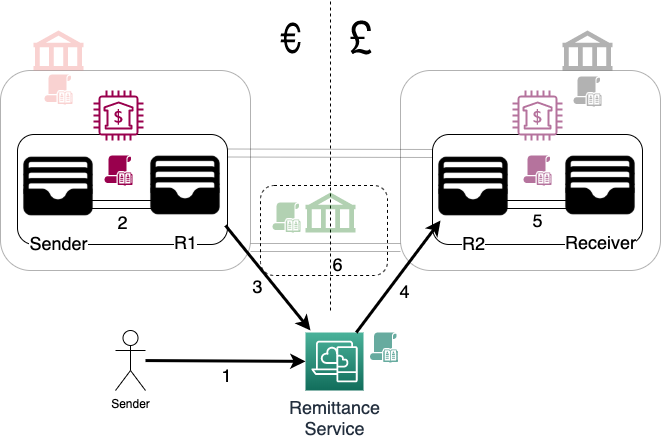

A practical example will help understand their modus operandi.

The Sender having an account in RedBank in the Eurozone, wants to send money to the Receiver. The Receiver has an account in PinkBank in the UK.

- Sender logs in to Remittance Service (RS) and enters her desired trade.

Say, send £100 to the Receiver’s GBP account. RS gets the current spot price and provides the details of its Euro bank account (R1). The transaction for now is still pending in RS’s ledger. Let’s say that the spot price means that Sender will “pay” €110. Sender has an alloted amount of time to send the funds, or the transaction is voided. - The Sender makes the transfer (2).

This is usually a local transfer using the mechanisms described in part 1. - RS gets a notification that the amount has been deposited in its R1 account.

The transaction is marked as “funded”. - RS then instructs its GBP account (R2) to pay out the £100.

- Again using a local payment mechanism (e.g. Faster Payments in the UK), Receiver gets the money.

The transaction is then marked as completed in RS’s ledger and the books are balanced. Notice how the Receiver got paid without an international money transfer.

Let’s pause here and unwrap the phrase “the books are balanced”.

In step 2, RS’s account R1 received €110, so RS’s assets increased by €110. By sending out the equivalent amount in GBP

in step 5 (i.e. £100), RS no longer owns the €110. Or better own the value represented by €110. By nominally “securing”

the FX rate at the moment of transfer (€110 for £100):

- R1 is up by €110,

- R2 is down by £100, and

- the books are balanced.

This is called netting off of flows.

This setup greatly accelerates cross-border transactions, as there is no need for expensive SWIFT messages or slow

nostro/vostro movements. The only requirement is that account R2 has the required cash buffer to service the payouts in

that currency.

The importance of the FX rate comes into play when we have the reverse flow.

Let’s say that 5 days later Receiver realizes this was a mistake and she wants to return the received £100.

The steps are followed in the reverse order. Meanwhile, Brexit has happened and GBP has lost its value relative to the

Euro. So now when RS gets the new spot price, £100 now buys €100.

At the end of the second payment:

- R2 is up by £100,

- R1 is down by €100, and

- the books are again balanced.

RS’s books are balanced, even though it was left with €10 in the end in its R1 account!

In this simplistic example, the currency flows resulted in an effective price arbitrage. In real life, the multitude

of daily movements in both directions would dilute this effect.

RS takes a fee out of each transaction as an FX merchant would, but actually moves a fraction of the transacted amounts.

The fraction actually moved as a “real” cross-border payment is dependent on the balance of payments between the

2 currencies. If the flows between Euro and GBP are balanced over time, then the balances of R1 and R2 will find an

equilibrium and RS will not need to move money between them. If we imagine that there is an imbalance of 5% more payments

Euro-to-GBP than GBP-to-Euro, then R1 will be needing a periodic 5% topup.

Depending on the size of the short-fall this can be covered in any number of ways.

- A periodic international payment from R2 to R1 to re-balance the books (line 5).

The FX fees paid by RS will be for a fraction of the fees it has collected for the total flows. - Interest accrued on R1 (if local regulation allows RS to profit from effectively customer assets), or

- Local borrowing (if the cost of debt in that market is really-really cheap).

In short, the more balanced a currency pair, the more profitable for the RS.

Some currency pairs are more imbalanced than others.

This is especially the case in the personal remittances market, where emigrants send money back home (e.g. from USD to

Mexican Pesos). This is one of the reasons why, past a certain size, all remittance providers try to expand into the

business payments market: to balance their flows.

Business and trade are in general more balanced. For example, countries with high emigration are usually net importers.

So the money entering the country as remittances, leave it soon after to buy cars and electronics.

This elaborate setup is nothing more than the digitization of the ancient Hawala networks.

…and the future

Digital IOUs

The world of cross-border payments is so complex and inefficient that it should be expected to have a blockchain-based solution: digital IOUs.

In this section I will only discuss Ripple. The alternative Stellar network has very little differences.

Its main difference to Ripple is that it tries to avoid the centralisation of funds by a distribution schedule.

The public Ripple network has all the components to be an all-in-one drop-in blockchain replacement for

- global nostro-vostro accounts,

- FX markets, and

- the SWIFT network built on top of them.

By extension, a private Ripple network (i.e. a network deployed from source code) is effectively a Hawala network out of the box.

The fundamental concept underlying Ripple is that of liability and debt, a.k.a. an IOU.

We mentioned in part 1 that paper money came from Kinghts Templar and merchant promissory notes, all of which

were forms of debt. Since mutual debt “cancels out” 4 everyone could be (and are indeed)

performing financial transactions, simply by owing each other value, without money actually changing hands.

This is what is actually happening in the real world. The modern day equivalent of the medieval Italian traders’ networks

are cross-border nostro-vostro accounts.

There are 2 missing ingredients in the equation:

- What type of debt do you trust?

Like in the real world, in Ripple you can have many different types of issued “paper” (called Ripple currencies). This is debt denominated in those currencies. However, a Ripple currency can represent anything of value, not just USD and GBP. As a participant, you can choose which “currencies” to trust. - Whose debt do you trust?

As in real life, you do not trust everyone’s promises. Which network participants do you think issue “paper” which they will make whole? Ripple solves this by introducing the concept of trust lines between accounts.

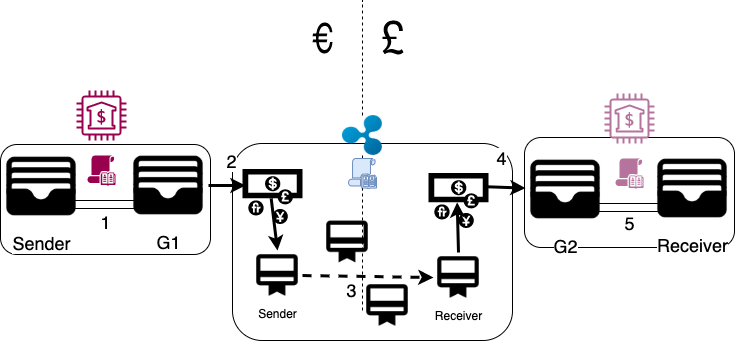

Let’s see how it works in a practical example.

Sender wants to makes a cross-currency payment to Receiver.

- The Sender has a Ripple account, which needs to be funded.

To do so, the Sender uses a gateway she trusts to convert her Euro fiat into “Ripple EUR” IOUs. She does so by funding the gateway’s collateral bank account (G1). - The gateway sees the deposit in the bank account, creates the equivalent amount of “Ripple EUR” IOUs and funds the Sender’s account. The Sender has a trust line with the gateway, i.e. she trusts the issued IOUs.

- The Sender makes a payment to the Receiver.

The Sender and the Receiver do not need to be directly connected by a trust line. Instead, the Ripple network finds a path of trust lines connecting the two. This is the same way that SWIFT finds a path of nostro-vostro accounts to facilitate international payments.

The transaction is then propagated through 5 the connected accounts until it reaches the Recipient. In Ripple-speak the transaction “ripples” through the network of accounts, with all balance adjustments recorded in Ripple’s distributed ledger.

When the transaction is a cross-currency one, Ripple provides a singular decentralized exchange where interested parties can transparently submit bids/asks on currency pairs. Ripple/XRP (i.e. the crypto-currency) exists as an intermediate “reserve currency”, to facilitate exchanges between “exotic” pairs. 6

In our example, the payment has resulted into a conversion from “Ripple EUR” to “Ripple GBP”. - Once the Receiver has received the payment of “Ripple GBP”, she can choose to take this to the issuing gateway 7 and convert it to “real” GBP. Once the right-hand gateway receives the “Ripple GBP”, it “burns” it and takes it out of circulation 8.

- The money is then transferred out of the gateway’s collateral account (G2) to the Recipient.

From this example, it is clear that Ripple is an on-ramp / off-ramp system.

It solves many problems of the international payment networks we have discussed quite elegantly through the use of

the blockchain.

In addition to some questions on its consensus algorithm resilience, there a few more issues with the public Ripple network’s design, both inherent and acquired.

Monetary imbalance

At its core, there is a “monetary imbalance” in the public network’s design.

Gateway IOUs are the equivalent of stablecoins (see next section), their value pegged to real-world currencies.

They are created/burnt on an one-in-one-out basis. XRP itself is arbitrarily priced in the open market and not

pegged to (or backed by) anything. Quite probably the designers aimed for the central “reserve currency” of the network

to reach an equilibrium with the global money markets’ demand. It would then draw its value solely by the utility of

the network itself.

However, this “backed by trust” label alone would not be very reassuring in an black swan / unwinding scenario (like the

one we are currently in).

Centralization of funds

The XRP crypto-currency is highly centralised, with over 50% of tokens in circulation controlled by a single entity.

This level of control along with criticism on lack of auditing transparency, gives cause for concern.

Centralization of control

Ripple network’s nodes are a closed set. Ripple Labs has a say on which entities can join the network as gateways and

may have undue control over the entire network. This is an intentional decision and part of Ripple’s strategy to

partner with existing financial institutions. This level of control however is anathema to the rest of the crypto community.

Based on the above one might think that digital IOU projects offer little value.

This could not be further from the truth. Though the economics and incentives of their public networks may

be open for debate, both technologies allow financial organisations with a cross-border foot-print (i.e. the Hawalas of

the modern age) to effectively create a robust payments network in a single sweep.

Stablecoins

Stablecoins are an interesting class of crypto-currencies, designed to maintain a stable value parity with another asset (e.g. one-to-one with a real-world currency, like the US dollar).

This is achieved in one of two ways.

-

Backed by real-world asset (e.g. USDT, USDC,…)

These are issued by an entity functioning in a way similar to the on-ramp gateways of Ripple. It receives currency in its bank accounts by users and issues the equivalent amounts of digital currency units. As with any IOU, their price has no reason to fluctuate, as long as the market believes that all digital coins have a real-world equivalent. -

Backed by digital collateral (e.g. DAI,…)

These stablecoins are minted when users deposit other crypto assets (e.g. Bitcoin, Ethereum,…) to a smart contract. Since the digital collateral has itself a fluctuating price, this class of stablecoins achieves a virtual peg by an elegant set of market incentives.

At their core, stablecoins are also on-ramp/off-ramp systems.

Their main use case so far has been to facilitate electronic crypto-asset trading, offering a stable digital unit of

account in a super-volatile asset class.

This stability combined with the benefits of the blockchain gives them a great potential to become a global medium of

exchange. This has not gone unnoticed.

Libra

Libra is, according to its website

A simple global currency and financial infrastructure that empowers billions of people.

In practice, it combines some of the concepts mentioned in the previous sections to offer a blockchain-based payment network.

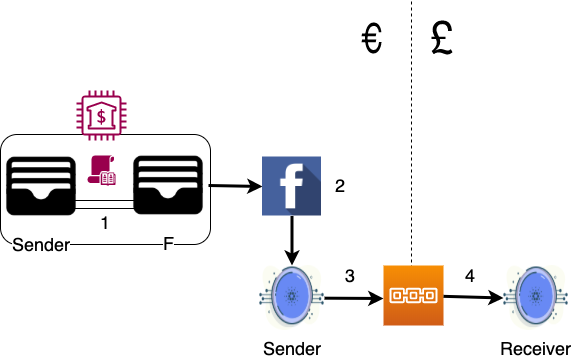

Let’s quickly examine how Libra works as a payment mechanism, making some simplifications for brevity. I will also not

touch upon its smart contract functionality, as it is out of scope.

A Sender wants to send an amount of €100 to the Receiver. Both of them have Calibra or another compatible wallet

installed.

- Sender needs to fund her wallet with the Libra equivalent of €100.

For this reason she sends €100 to Libra gateway’s bank account (F) 9 - The Libra gateway is notified of the amount and creates the equivalent amount in Libra. It then funds the Sender’s wallet.

- Sender can then use the Calibra wallet to issue a blockchain payment.

The payment is sent to the network, the blockchain nodes of which are run by the partners. - …and a few seconds later the Receiver sees her Libra balance increasing.

If the above looks very familiar, it’s because it is!

At its core Libra is not a currency. It is a fusion between an IOU and an asset-backed stablecoin. The novelty here is

that it is backed by a basket of currencies, reducing currency risk.

Steps 1 and 2 are the on-ramp to the platform. What is missing on the other side of this diagram is the off-ramp, where

Libra would be converted to GBP.

The on-/off-ramp is described in the reserve policy as “a network of authorized resellers”.

We have seen previously in monopolistic digital currencies, like M-Pesa, how there are off-ramp penalties to discourage asset

flight. The project’s vision has been that of a global currency, bank the unbanked etc. Facebook’s user base guarantees

that the currency will have the required network effect from day 1. Users would not feel the need of the off-ramp. Perhaps

an “exit tax” might be another nudge to stay.

The technical merits of the system have been eclipsed by the aggressive marketing blitz focusing on global currency and

the subsequent regulatory backlash. A global stable currency, takes away the only thing that makes a government, well… a government. All this

at a time of geopolitical tensions, even before the Covid-19 black swan, this was not the right message.

Why not baptize it as a remittance service, a digital IOU,… something fairly conspicuous, woke-ish and under

the radar? Facebook already had the partnerships in place to make it a de facto global payments network overnight.

I honestly do not know what the future of this project is.

But I think Libra ticks many boxes to become a case study for Silicon Valley’s detachment from the “real world” and how

it works.

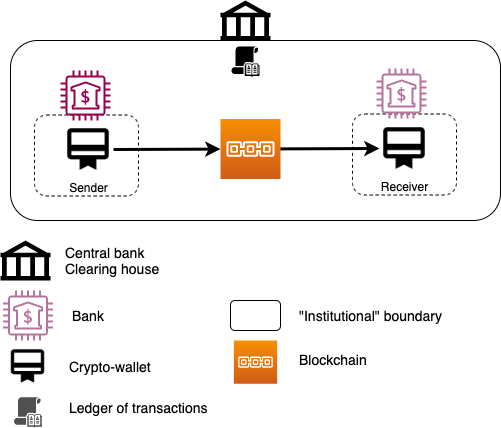

Government cryptocurrencies

The last few years have seen an increasing interest in the replacement of fiat currencies with central-bank issued crypto-currencies.

The underlying payment mechanism in such a case would be extremely simple.

- The Sender has a crypto-wallet on her device, possibly provided/facilitated by a commercial bank.

She issues a payment to the network of trusted nodes. This network will almost certainly be non-public with the compute capacity owned entirely by the central bank or with the national retail banks all offering hash power. - The payment is attached to a block in a way similar to how existing blockchains operate and confirmed by the network.

- At this point the Receiver’s wallet has received the amount.

The transaction has been immutably recorded in the network’s distributed ledger.

One might wonder “payments are pretty much electronic now, why bother with the crypto stuff”? The answer is definitely above my paygrade but I will offer my limited understanding.

Transactions are increasingly electronic, but not 100%.

There are also stores of value outside of the “system”, with cash and precious metals/stones being the prime examples.

It is not by co-incidence that

- capital controls immediately restrict access to cash, and

- all countries impose limits on the amount of valuables one may export. 10

India’s 2016 demonetisation was a huge social experiment, observed with very keen interest from central bankers around the world.

In an insitutionalized crypto-currency environment fiscal policy becomes almost trivial. Taxes are not new in human history and states have an ever-growing appetite for revenue. 11 Having all transactions visible in real-time and recorded immutably forever has a very-very particular allure. 12

In the same vein, the elimination of cash and intermediaries (a.k.a. banks) opens up endless creative possibilities in

the area of monetary policy.

Why fight with ever-lower interest rates and bother with QE and trickle-down economics, when you have seen it cannot

create real inflation? 13 Why not send an airdrop (a.k.a. helicopter money)

straight into people’s crypto-addresses?

Why not make it more interesting and force velocity of money by making this newly acquired crypto-money auto-burn every few days? 14

Why worry about the debt crisis when you can have centrally controlled and auto-adjusted debt margins and jubilees?

It is common knowledge that the current system is well overdue for a reset due to excessive monetization. In less than 12 years it has gone from a banking crisis to an unfolding debt crisis. The current Covid-19 pandemic is merely the needle to pop the balloon.

The government and central banks’ answer to the previous crisis was more control.

MMT approaches have well entered the Overton window of economical orthodoxy and will be deployed in the

next few years. The current virulent outbreak and consequent recession / depression will only hasten their arrival.

Government crypto-currencies are the perfect tool to deploy such policies.

Proof-of-work money

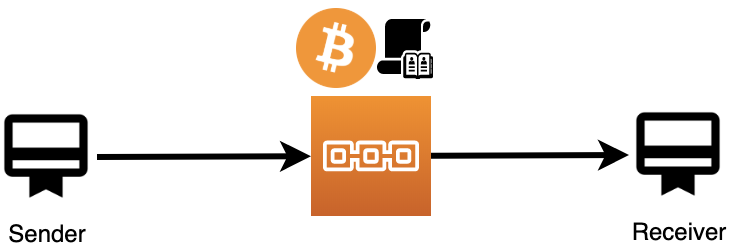

The last payment mechanism in the series is also the simplest one: proof-of-work (PoW) money.

The Sender signs a payment with her private key and sends it off to the public network.

The miners reach a consensus on the validity of the transaction and it is immutably recorded on the shared

ledger. Value has been transferred to the Receiver.

There are on- and off-ramps in the form of exchanges, but these are purely utility mechanisms. They facilitate onboarding from the existing fiat world, but are not critical the same way an on-ramp Ripple gateway is. Unlike Libra/stablecoins/etc, PoW money is not created at the gateway. It exists in and of itself, created as reward for capital and operational expenditure to mine it. This value is “locked” inside the system, behind the “hashing wall”.

The best approximation is that of physical precious metals mining.

All the gold that was easy to mine has been found and exists above ground. It now becomes increasingly expensive

to dig out more. Unless a gold meteorite lands on Earth, that spent capital remains “locked” inside each ounce,

making it irreplaceable and valuable.

From that aspect, the major PoW cryptocurrencies are the best digital equivalent of money, as I described it in part 1.

Those with a high network hashrate and fixed supply / scarcity become true assets. True assets meaning that they have value

without an underlying claim to “something” or the need for a trusted third party.

They are the purest digital equivalent of in-person transactions, but for a global scale.

Though PoW currencies by themselves may not be THE answer, they may be the core underpinning of a new payments

infrastructure (backing collateral, akin to digital gold).

Some racing thoughts

Photo by San Fermin Pamplona - Navarra on Unsplash

In these 3 articles (part 1, part 2) we saw how the transfer of value has evolved over millenia.

From a simple hand-in-hand transaction in the olden days, to national payment networks, mobile money, complex global

banking systems and “value routes”.

As we were describing these systems, you may have noticed a couple of common patterns emerging.

Trust

The existing payment systems’ fundamental shortcoming is that of trust.

In the digital payment space, trust can only be effectively established on a bilateral basis. This is how

nostro/vostro accounts came about. If that is not enough, then a “neutral”, trusted third party is needed for additional

guarantees and oversight. This third party is usually de jure, enshrined in law or international agreements.

However, this is not very different from person-to-person transactions. A problem of the small scale has been replicated

on a larger one.

Layering

The second pattern is that of additional layers. Newer networks and payment rails are layered on top of existing

constructs.

Debit/credit cards cannot operate without an underlying bank account and payment network. SWIFT cross-border payments

cannot operate without the underlying complex web of nostro-vostro accounts.

The old systems’ inefficiencies are merely papered over with a layer of technology and cash buffers as collateral. These

facilities are provided by yet another third party (the payment provider), which becomes trusted. This third party is de facto, imposed

by market forces.

These issues have been addressed both at once with the introduction of blockchain.

Blockchain is effectively an automated, distributed trust machine, allowing multiple unrelated parties to transact.

This is self-evident in the simplicity of PoW payments, compared to the layers and layers of complexity of the current

systems.

In addition, every possible monetary policy has been modelled and exists now in the crypto-currency space: from fixed supply, to

fixed inflation, to deflation, to asset-backed and everything in between. This Cambrian explosion is a stark

contrast to the current fiat monetary system’s stagnation in the face of uncertainty.

Until recently, a “regime change” in the global payments and monetary system was very likely. This would

probably involve replacing fiat with a crypto-based system (almost certainly government controlled, almost unlikely

decentralized).

The current Covid-19 outbreak, along with

- the massive stimulus packages,

- helicopter money arrangements which have started, and

- the upcoming debt and retirement crises

are making this inevitable.

The only remaining question in my head then is what would be the role of today’s banks and payment processors in this

new landscape?

Would they continue as the pillars of the system, being used to distribute the newly minted cash? Or would they shrink

beyond recognition? Even without the current debt crisis 15 the current trend was for banking

to be “democratized”.

Banking services have been dispersing across the economy with 100s of companies becoming banks in all but name.

In a fully crypto world, what would even be the role of banks?

Would they be only providing KYC and simply be custodians of wallet holder personal information?

Could they become one of the m-of-n custodians in a multisig government crypto-currency wallet, essentially

only holdινγ some private keys in their vaults??

Would they be the trusted node operators and notaries in a Corda-like network?

How can they justify their importance as lenders when current DeFi systems are operating through great volatility

and with a tiny fraction of operating costs?

The same questions (and more!) apply to payment processors.

The next state of the payments world is inevitably going to be based on the blockchain.

This can be the crypto equivalent of government fiat currencies or asset-backed “tokens” (e.g. moving to back to the

gold standard or to a new Bitcoin standard). In any case it seems almost certain that the current

shrinking trajectory of retail banks will only accelerate. Banks and financial institutions in general will likely

end up as a tiny fraction of their current size and importance. In a blockchain world of digital identities maintaining

alternative channels 16 and being systemically important is beyond pointless.

The upcoming evolution of the global payment networks will probably be an extinction event for the majority of

the current financial system.

What will remain after will be hardly reminiscent of what was there before.

Footnotes

- E.g. half of Kenya’s GDP is processed through mobile payments.

- AliPay is the payment rail originating from the B2B platform Alibaba. It is a bit of a stretch, but I am including it here nevertheless.

- E.g. chatting in WeChat, ride hailing in GoJek. A.k.a. as the thin end of the wedge strategy.

- If I owe you 10 and you owe me 10, we owe each other nothing.

- Sender says to Joe “Pass £10 on to Recipient and I owe you”. Joe says to Jane “Here is the £10 that I owed you, pass it on, please”. Jane says to Jack “Here are £10 for Recipient, add it to my debt”. Jack finally says to Recipient “Here is £10 from Sender, you now owe me”. This is better visualized and explained here.

- This is the same role that the US dollar plays in the real-world FX markets and cross-border payments.

- Just as “Ripple EUR” was issued by the left-hand gateway, “Ripple GBP” has been issued by another gateway. This is what is converted in the Ripple exchange: one type of IOU for another. It is not “magic’ed up”.

- Same way you rip a debt certificate once the debt has been paid off.

- Here I am over-simplifying in multiple ways. Yes, Libra is a foundation, not controlled by Facebook. Also in real-life the payment would be facilitated via card, OpenBanking or some other mobile-friendly way. And according to the stated reserve policy, purchase of Libra would be via a network of resellers.

- Yes, illegal activity is also a concern, but it is the central bank’s balance sheet that counts. Imagine the Argentinas and Greeces of the world if their citizens could take their assets’ worth into gold to a more stable place.

- Say your unit of labour gives you £10. You are taxed at source with, say, £3. Then you buy a T-shirt and pay VAT. Then you put the remainder towards a house and pay stamp duty, etc. Even though you worked once, your work’s result (i.e. your salary) will be taxed multiple times, every time that a fraction of it changes hands.

- Why wait for the end of the quarter or the fiscal year to see if tax reduction has boosted

business when you can see it the next minute?

Why reduce taxes for all businesses when you can see that the economic slow-down is from a few crypto-addresses in the Barcelona area? Just reduce taxes for them.

Not to mention the amount of information revealed by such a panopticon payments network. - The only inflation QE and negative yields have caused are in asset prices. In simple words: you have not had a noticeable pay rise in forever, TVs and blenders are becoming better and cheaper and, yet, houses, gold coins and Netflix shares become ridiculously unaffordable.

- I.e. use it or lose it. It may sound impossible to create in the current regime, but in the world of smart contracts it is almost trivial to implement.

- Or maybe because of it.

- Branches, ATMs, mobile banking, telephony, cheque processing,…